|

Summary

The NEP was not the ‘island of

freedom’ it is sometimes made out to be.

Infancy and Childhood: The NEP improved infant survival rates due to better maternity hospitals and hygiene campaigns. However, education suffered – funding cuts led to school closures and

tuition fees. By 1928, only 60% of primary-age children were in school, with rural access especially poor.

War and famine left 500,000 street children, many in poorly equipped homes or

OGPU-run labour communes where conditions were harsh.

Youth: The Bolsheviks tried to shape youth into ‘New Soviet Man’ through organizations like the Young Pioneers and Komsomol, which promoted political activism and anti-religious campaigns.

However, Komsomol remained small (only 6% of youth by 1926, and girls faced

exclusion and abuse), and many young people preferred Western culture, fashion,

free-spirited communes and ‘hooliganism’ … to the horror of the authorities.

Women: Early Bolshevik laws promised equality, but returning soldiers displaced women from their jobs, pushing female unemployment to 70% by 1923. The Party prioritized state needs over gender rights, and the promised childcare and domestic support developed only slowly. In rural areas, female activists faced hostility, and a forced unveiling campaign in Central Asia met violent resistance.

Peasant women, also, often opposed Soviet policies, fearing new divorce laws

would further divide landholdings.

The Village: Some modern amenities – electricity, hospitals, libraries, and cinema – reached rural areas, but remained sparse. Though the NEP’s replacement of grain requisitioning with the prodnalog was an improvement, their tax burden remained high, including labour obligations and indirect taxes. Peasants suffered the ‘Scissors Crisis’ – fixed grain prices remained low while industrial goods’ soared.

Attempts to introduce modern farming techniques and cooperatives met resistance,

so Soviet propaganda targeted rural youth, encouraging them to challenge

traditional elders, and organised 'rural correspondents' to write letters to the

newspapers recommending change.

The Towns: Historians write that cities bustled with trade and recreation, but the NEP also included decadence, gambling, corruption and waste, prostitution and crime.

Social inequalities widened as engineers and technicians gained high salaries

and privileges, while ordinary workers struggled.

The NEP was never a capitalist interlude: the State kept control of the major industries, 84% of workers work in nationalised industries, and the Nepmen were despised and hassled.

And it failed; by 1929 there were long queues for consumer goods.

In what ways were the lives of Russians affected by the New Economic Policy?

The traditional interpretation of life under the NEP, especially in the Western world, is exemplified in Katherine Eaton’s 2004 comment – that the NEP was:

“an island of relative calm and prosperity in a sea of troubles that stormed over Russia and the Soviet Union from the beginning of one World War to the end of another.”

But how true is this? In 1988 the British historian

Robert Service judged that, whilst admittedly not as awful as the horrors of War

Communism which preceded it, or Stalin’s Terror which followed it, life under

the NEP – at least for opponents of the regime – was still “grim”.

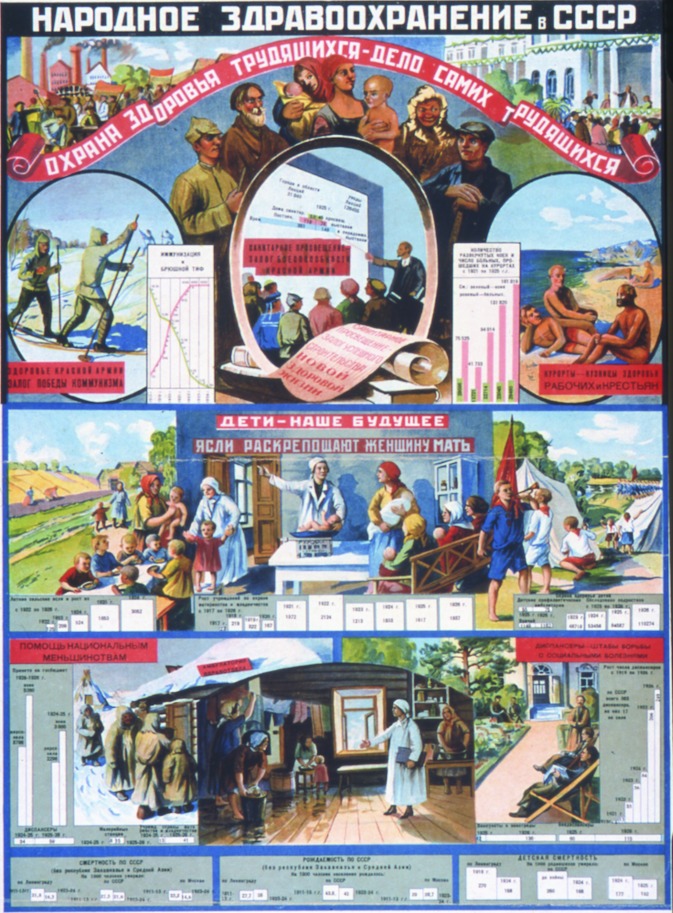

This 1927 poster – People’s Health Care in the USSR – by the

Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia celebrates the NEP's

achievements.

The banner reads "The Protection of Workers’ Health is the Responsibility of

the Workers Themselves", and three cameos in the top section show, on the left,

healthy exercise; in the centre, a bureaucrat (looking a lot like Lenin) and

workers engaged in discussions, with a large scroll detailing healthcare plans;

and on the right; healthy workers able to relax.

In the centre, under headings reading "Children are Our Future" and

"Nurseries Liberate the Working Mother", we see a nursery, a doctor giving

instruction in child care, and a Young Pioneers camp.

The bottom panel highlights "Assistance to National Minorities" and shows a

delivery of medical aid, a doctor visiting a peasant's home, and a hospital.

Infancy and childhood

So how were the lives of Russians affected by the NEP?

Well, for a start – literally – as a result of the work of Nikolai Semashko and the People’s Healthcare Commissariat – you had a 16% better chance of surviving your first year of life in 1925 than a baby born in 1915.

You had to be in a population centre to have access to one of the Commissariat’s

maternity hospitals, infant-feeding centres or day nurseries but, even in the

countryside, education and a massive propaganda campaign were improving general

standards of hygiene and sanitation.

After that, however, childhood was not as good as it had been. Funding for primary education actually fell in the early years of the 1920s, and schools closed, or started to charge fees; the number of children in education and the number of schools halved in the first 18 months of the NEP. Even by 1928 only 60% of Soviet children of primary school age were in school, and – if you lived in the countryside – you were unlikely to complete even three years of education.

Secondary education was even worse – the big Soviet push for literacy was aimed

at adults, particularly the Red Guard.

Moreover, as a result of the war and the 1921-22 famine, half-a-million children in 1921 were

besprizorniki (street children) who had been orphaned or ‘given to Lenin’ (ie abandoned). Those that could be caught were housed in one of 6,000 children’s homes or in labour communes run by OGPU. Facilities were poor, food short, treatment rough, and mortality extremely high.

Government policies had not caused this problem, but they failed to contain it.

Youth

The Bolsheviks had had high hopes for their youth, who were to grow up to be the ‘New Soviet Man’. At age 7, a child might be made an

oktyabryat (child of October) and given a badge. At school they sang

songs inculcating revolutionary principles

and at 9 they became ‘Young Pioneers’.

Finally, for young people aged 14-28, the Bolsheviks had set up a youth organisation called Komsomol.

By 1926 it had 1¾ million members (though this was still only 6% of the youth

population).

A Komsomolet promised to be “a lively, active, healthy, disciplined youngster who subordinates himself to the collective and is prepared for and dedicated to learn, study, and work” – it was primarily a political activist organisation. Lenin urged them to grow vegetables, promote public hygiene, distribute food and conduct house-to-house inspections.

Club leaders organised rallies and marches, particularly to harass church-goers

– fun and a sense of purpose if you liked that sort of thing.

Not so good for girls, though. Girls were encouraged to attend, but many were forbidden by their parents, since meetings were held at night. Those who did attend found a testosterone culture which excluded them from leadership and exposed them to “uncomradely conduct”,

and female membership declined from 21% in 1922 to 12% in 1925 (though some

Komsomol branches ran successful home economics, knitting and literacy circles,

and arts & crafts courses).

Other young people joined the Red Army; after 1929 they

returned to their villages to impose collectivisation, evict their parents and

kill the kulaks.

For most Russian youths in the 1920s, however, much more attractive was ‘hooliganism’, and Western cinema, magazines, fashion and cosmetics. Some young people dropped out to live in communes, where members declared that – since the Revolution had destroyed all the old rules – they were free to do as they pleased with their sex lives, and they engaged in free love and same-sex love (which had been decriminalised).

Abortion and divorce ballooned.

Most Russians found all this sort-of-behaviour scandalous,

and by the end of the NEP, the Soviet authorities were taking steps to censor

and suppress ‘deviant’ western culture in the youth.

Women

A slew of decrees in 1917-19 – eg on Women’s Rights; a Code on Marriage, Family & Guardianship; the Family Code – had enacted the Bolsheviks’ principles for women.

A Department for the Protection of Mother and Child was created (1917), the

first National Women’s Congress held (1918), and the Zhenotdel

established (1919).

So did women’s lives improve? In 1925, Zherebtsova, a peasant woman from the Urals wrote to the peasant women’s journal,

Krest’ianka:

“Previously women lived in the dark and dirt, suffered beatings from [their] husbands, knew the priest and the kulak, and the last bit of butter was taken by the priest and the kulak... The Communist Party conducts hard work among the peasants. The peasant woman awakens, learns, and strives to improve her economic situation.” Reality, however, was less deferential. Five million

soldiers came home in 1922 and the government – in a coded message which

instructed government concerns to be more ‘efficient’ – encouraged state

factories and the civil service to lay off women in favour of men; by 1923,

women made up 70% of the unemployed.

The men who ran the Party believed theoretically in ‘women’s equality’, but thought of it in men’s terms, valued the traditional household, distrusted feminism, and wanted women mobilised for the benefit of the State, not for the benefit of women.

The promised childcare and domestic facilities materialised only slowly, and

women's political participation remained limited.

In the villages, Zhenotdel activists were often shunned, verbally abused, and made to leave, and an ‘unveiling’ campaign in Muslim central Asia caused a violent backlash. The Bureau faced apathy and opposition from within the Communist Party, until in 1930 Stalin transferred its operations to Agitprop.

Peasant women were just as likely to reject Soviet principles as the men,

especially when the most the government seemed to be doing was setting up mutual

encouragement groups; they realised that the new divorce laws splitting property

equally would further divide plots which were already too small, and they stayed

with their husbands.

The Village

Orlando Figes (1996) believed that there was some ‘trickle down’ of modern amenities – electricity, hospitals, theatres, libraries, cinemas – into the countryside during the NEP, and there is certainly evidence that this might have been the case:

- In 1927, the Soviet Information Bureau announced that, where there had only been only 75 power plants for rural areas in 1917, there were now 858, supplying 90,000 farms, and “a beginning has been made to applying electric power to agricultural work, especially in relation to such things as threshing machines, flour-mills, fodder cutters, grain cleaning machinery, sawmills, oil pressing plants, etc.”

- A quarter of the country’s 250,000 hospital beds, and

a third of its maternity beds, were in rural areas.

- In 1924 the Soviet Union had 13,500 libraries (8,600 in rural locations) with a total of 62 million books and 17,000 staff.

In addition, there were 11,000 ‘reading huts’ for adults, supplied with

radios and movies.

- And, even where there were no theatres or cinemas,

Agitprop trains were taking film-shows to everywhere there was a railway.

These figures are small, given the huge size of

Russia, and you need to take into account that the population of Russia grew 13%

1921-26, spreading facilities even more thinly … but it shows that modernity was

beginning to seep into areas of countryside life. Were the villagers any better off? Historians would tell you that replacing the

prodrazverstka by the prodnalog was a massive improvement, and indeed one of the requirements of the 1921 Decree which instituted the tax-in-kind was that: “This tax must be less than what the peasant has given up to this time through requisitions”. Nevertheless, it was a substantial burden, and to it have to added be a 6% compulsory participation in the State Lottery Loan, compulsory labour (mainly on the roads), and indirect taxes on a wide range of goods, including tobacco, matches, alcohol, sugar, starch, tea, coffee, salt, rubber shoes and textiles. The British economist Margaret Miller, surveying taxation in Russia in 1925, commented that, although the burden of tax-per-person was half what it had been before the war, “the taxpayers find it more than twice as difficult to bear, owing to the shrinkage in the great majority of incomes”.

This was especially the case because – whilst the government fixed the price of

grain at 1914 levels – the price of the industrial goods that the peasants

needed had risen by multiples (the so-called ‘Scissors’ crisis’).

The other factor to be taken into account is that, in 1923,

the tax-in-kind was commuted to a money payment – the peasantry were thus being

forced towards the new, commercial, age.

Meanwhile, the People's Commissariat of Agriculture (Narkomzen) was trying to impose modern farming methods upon the villages – there was some rationalisation of strips, and some experimenting with new rotations & fertilisers.

By 1927, 50% of all peasant households belonged to an agricultural cooperative.

There was, in many villages, immense resistance to these new ways, and the

Narkomzen struggled to make headway. What one has to realise is that the peasant revolts had not just worried the regime – they had defeated it.

The peasants had declared independence in 1921, and grew more not less

independent under the NEP – thus the Bolshevik regime, under the NEP, was quite

as much ‘at war’ with the peasantry as it had been under War Communism … it was

just waging that war in a different way.

The Bolsheviks, unable to impose communism on the village hierarchy, sought to undermine it. Young people, in particular, were the target of Bolshevik propaganda, and there is evidence that in the 1920s they were beginning to challenge the village elders, whose ways they felt were holding the village back.

Under another disruption initiative, selkors derevenskiy (‘rural

correspondents’) were encouraged to write (thousands of) letters to the

newspaper Krest'ianskaia Gazeta about their efforts to make their

villages new and Soviet (so now we know where Zherebtsova was coming from) …

including criticising local elders and officials who were holding back progress;

perhaps understandably, they sometimes found themselves under attack from the

victims of their criticism.

All told, however, the Bolsheviks seem to have made little progress in the countryside during the period of the NEP.

By 1927 production had stalled and they were realising that they were losing

their attempt to defeat counter-revolution by economic means & propaganda … a

realisation which led to Stalin & collectivism.

The Towns

It is a staple of the traditional interpretation that the NEP galvanised urban life, and both Sheila Fitzpatrick

(1988) and Orlando Figes

(1996) described a bustling city life of trade and recreation.

To a degree, this is special pleading. Both Fitzpatrick and Figes owe some of their accounts to that of the anarchist Emma Goldman, who was NOT an eye-witness, and wrote her description of hungry people gazing into the windows at a decadent lifestyle as a criticism … and she went on to describe the negatives of the NEP – the persecution of opponents, the emasculation of the trade unions, the subordination of the Soviets and the cooperatives to the State, the glaring social inequalities, “the reversal of Communism itself”:

“While the workers continued to starve, engineers, industrial experts, and technicians received high salaries, special privileges, and the best rations. They became the pampered employees of the State and the new slave drivers of the masses.”

Another critic of the glaring class inequalities of the NEP was the leading Menshevik Fydor Dan.

American journalist Walter Duranty – who was an eye-witness – although he stressed “the immense stimulus [the NEP] gave to employment of all kinds” and told the story of a street-trader who through honesty had built up a chain of small stores – nevertheless saw (and experienced first-hand) the “seamy” side of the NEP: “its reckless gambling and easy money, its corruption and license” and “the low-class jackals and hangers-on, with fat jowls and greedy vulpine features” who frequented the club called ‘the Bar’ or, worse, the the Red Light district.

Reading Duranty, the NEP seems more like a Wild West boom-town than an

entrepreneurial revival.

Moreover the Nepmen, the vanguard of the NEP, were not as protected as is sometimes inferred. They were officially class enemies, constantly subject to arrest, the target of high taxes and hostile propaganda, and harassed by Komsomol.

Public attitudes towards the Nepmen were revealed at one Comrades’ Court at a

print workshop, which considered the case of a female Komsomol member who had

secretly married a Nepman (in a church!); it turned out to be a fictional

scenario, but not before the workers had decided to expel her.

In fact, the private traders and the Nepmen were never a capitalist interlude. The State still held onto what Lenin termed the “commanding heights” of the economy – heavy industry, transport, banking, exports – and 84% of the urban workforce still worked in nationalised industries. And, although we are told that

at one time private traders controlled 75% of the retail trade, the boom was short-lived: by 1929 that share had fallen to 20% or 30%, there was a crisis in retail sales and, as the German journalist Paul Scheffer reported: “people stand in line not only to buy many of the essentials of life, but even to get electric light bulbs!”.

The NEP, people agreed, supplied the goods, but only at a price … and that cost

was not just monetary.

|

|