|

|

NOTE: this topic is a stated topic on the AQA specification only. It is NOT a topic on the Edexcel or OCR specifications.

|

|

In 1897, Bernhard von Bülow – then German Foreign Secretary but soon to become Chancellor – announced in the Reichstag: “We wish to throw no one into the shade, but we also demand our own place in the sun." It was the beginning of the policy of Weltpolitik – ‘world politics’. You will remember that Bismarck had followed a careful foreign policy. Wilhelm and Caprivi had already overturned that policy in 1890 when they decided not to renew the Treaty with Russia. From 1897, however, Germany moved onto the offensive … in particular seeking to expand its empire overseas.

|

Going DeeperThe following links will help you widen your knowledge: Basic account from BBC Bitesize

YouTube Pete Jackson video - really good

|

Weltpolitik in Foreign Policy[Kickass Kaiser Becomes Fairly Annoying]

In Foreign Matters, Weltpolitik took the form of a series of humiliating failures, along with an expansion of the German Navy, which failed to gain any colonies, pushed France, Russia and Britain together into an ‘Entente’ against Germany ... and, in the end, played a significant part in causing the First World War. (Click on the u orange arrows to reveal more information)

|

|

Case Study: the Entry into Jerusalem, 1897

In 1897, Wilhelm visited the Ottoman Empire. He met the Sultan wearing military uniform. As part of the visit, Germany acquired the contract to build a dock in Istanbul, and also trade agreements for weapons, iron and steel. Wilhelm opined in public that the Sultan’s problems in Crete and Anatolia were due to British interference. Next, the Kaiser travelled to Palestine, where he met with German settlers there, and then entered Jerusalem.

Then to Damascus, where he gave a speech saying that he was not only the protector of Protestants and Catholics, but of 300 million Muslims. Writing about the visit, historian İrfan Ertan (1993) considers the visit an exercise in ‘soft power’ and the starting point of Germany’s Drang nach Osten [‘Drive to the East’] policy.

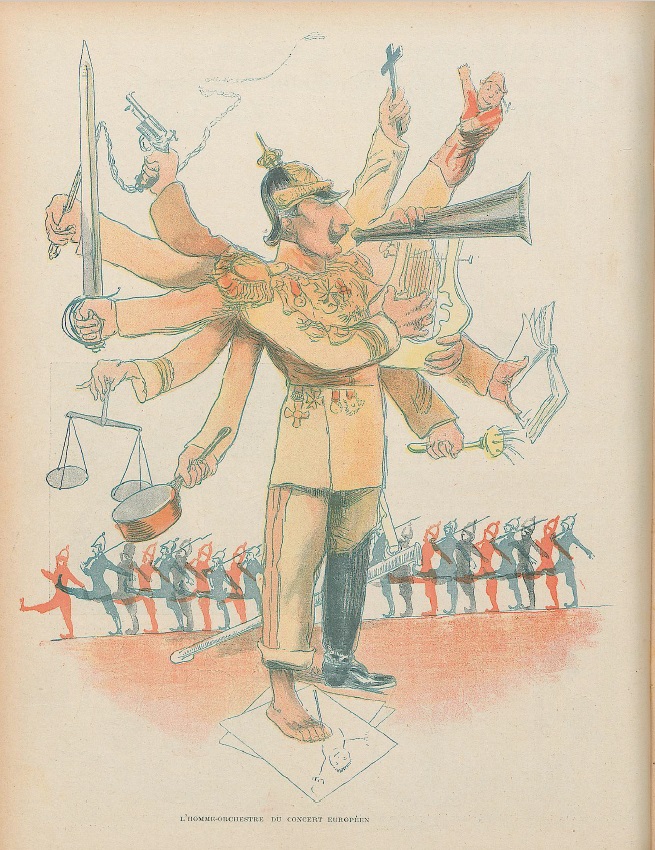

This illustration is entitled: 'The One-man Orchestra of the European Concert'. It comes from the French satirical magazine Le Rire ('Laughter'), a special issue of November 1898 dedicated to Kaiser Wilhelm's foreign policy and his visit to Palestine.

|

Consider:1. Looking at the satirical cartoon, make a list of the things Wilhelm is shown as holding. Each one represents an accusation - for each, suggest what Le Rire is accusing him of. 2. Thinking about the Kaiser's visit to the Holy Land in 1897, make a list of all the different parties he managed to annoy, and why?

|

Weltpolitik in Home Policy

It is important to realise, however, that Weltpolitik was also a key element of Wilhelm's 'Home Policy'. In domestic politics, Wilhelm hoped that Weltpolitik would win him support, as it would advance trade, but also appealed to nationalism. It was enthusiastically supported by Industrialists, the middle classes, and the Reichstag. A key element of Wilhelm’s Weltpolitik were Admiral Tirpitz’s Navy Laws, introduced 1898-1912 to increase the size of the German Navy. By 1914, Germany had built 44 battleships, 58 Cruisers, 72 U-boats and 144 torpedo boats.

BUT:

|

Source AGermany, wedged in between France and Russia, certainly had to be at least prepared to defend herself on the water against those nations. For this our naval construction program was absolutely necessary; it was never aimed against the English fleet, four or five times as strong as ours… The Skagerrak (Jutland) battle has proved what the fleet meant and what it was worth. That battle would have meant annihilation for England if the Reichstag had not refused up to 1900 all proposals for strengthening the navy. Kaiser Wilhelm in his Memoirs (1922)

Consider:1. Thinking about the Kaiser's interview with the Daily Telegraph, make a list of all the different parties he managed to annoy, and why? 2. Which bits of Wilhelm's comment about the incident in his Memoirs show that he did not admit any mistake? 3 Why were the Navy Laws introduced, and what part did they play in Weltpolitik? 4. How did the Navy Laws affect the Kaiser's relationship with the Reichstag? 5. "Weltpolitik ruined the Kaiser's reputation" - do you agree?

|

Case Study: the Daily Telegraph interview, 1908

On a visit to Britain in 1908, Kaiser Wilhelm gave an interview to the Daily Telegraph newspaper, in which – although he claimed that he wanted to be a friend to Britain – he said that the English were “mad, mad, mad as March hares” for making things difficult for him; that people in Germany were "bitterly hostile" to England; and that: "Germany must have a powerful fleet to protect her interests in even the most distant seas". This caused an uproar in Britain, where it was interpreted as an insult and a threat, but also in Germany, where those who hated Britain were angry he had talked of friendship, and those who did not want conflict with Britain realised that it was a direct provocation. As Wilhelm admitted in his Memoirs (1922): "A storm broke loose in the press. The Chancellor spoke in the Reichstag, but did not defend the Kaiser, who was the object of attack, to the extent that I expected, declaring, on the other hand, that he wished to prevent in future the tendency toward "personal politics" which had become apparent in the last few years. The Conservative party took upon itself to address an open letter to the King through the newspapers... "So also the Liberals of the Left, the Democrats and the Socialists, distinguished themselves by an outburst of fury, which became, in their partisan press, a veritable orgy, in which loud demands were made for the limitation of autocratic, despotic inclinations, etc. This agitation lasted the whole winter, without hindrance or objection from high Government circles."

Wilhelm had to send a conciliatory note to the Reichstag promising to be more circumspect in future.

|

|

|

| |