|

Source a: The importance of the vote.

It is important that women should have the vote so that, in

the government of the country, the woman’s point of view can be put

forward. Very little has been done for women by legislation for many

years.

You cannot read a newspaper or go to a

conference without hearing details for social reform. You hear about

legislation to decide what kind of homes people are to live in. That

surely is a question for women.

No woman who joins this campaign need give up a

single duty she has in the home. It is just the opposite, for a woman

will learn to give a larger meaning to her traditional duties.

From a speech

made by Mrs Emmeline Pankhurst in March 1908.

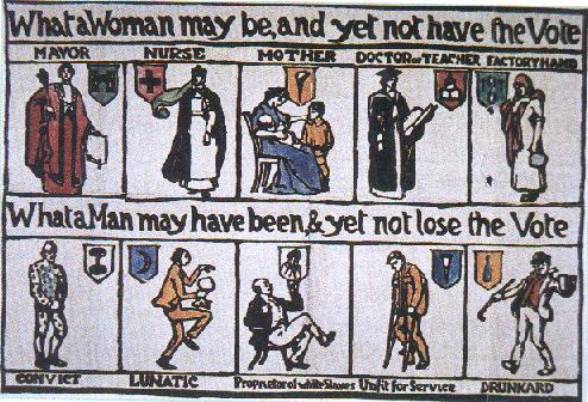

Source b: An argument in favour of votes for women

Source c: An argument against votes for women.

Women do not have the experience to be able to vote. But

there are other problems as well: the way women have been educated, their

lack of strength, and the duties they have.

If women did gain the vote, it would mean that

most voters would then be women. What would be the effect of this on the

government? I agree that there are some issues upon which the votes of

women might be helpful. But these cases do not cover the whole of

political life.

What is the good of talking about the equality

of the sexes? The first whiz of the bullet, the first boom of the cannon

and where is the equality of the sexes then?

From a speech

made in 1912 by Lord Curzon, a Conservative leader.

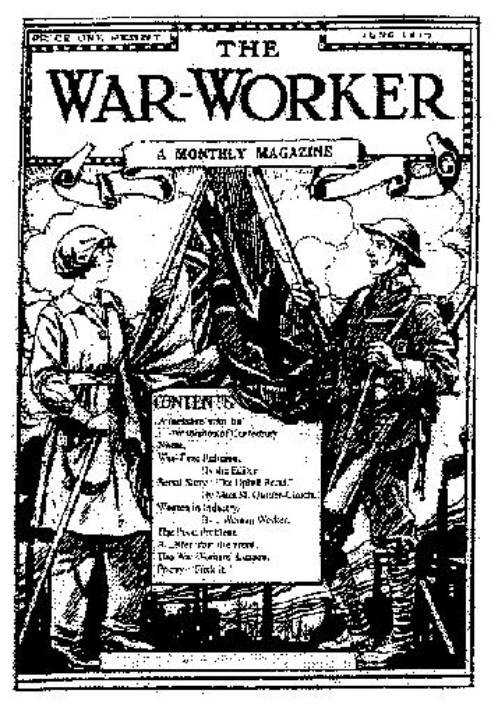

Source d: Men and women united in a common cause

The cover of

the War Worker magazine, June 1917

Source e: Male attitudes to women workers during the First World War

Attitudes to women workers remained, in many cases,

negative. The ability of women to take on what had been men’s work meant

that increasing numbers of males were vulnerable to conscription.

Some women doing skilled work had the full

co-operation of male employees. Many other women were restricted to less

skilled work and were victims of hostility and even of sabotage.

From War and

Society in Britain 1899–1948, by Rex Pope, an historian, 1991.

|